Rated PG: Getting back at it

- Details

- Published on 25 October 2017

- Written by Paul Gordon

Starting over can be a challenge, depending on the circumstances. But in my case, returning to work after nearly eight months on disability, it is a challenge I look forward to facing.

Starting over can be a challenge, depending on the circumstances. But in my case, returning to work after nearly eight months on disability, it is a challenge I look forward to facing.

Those of you who have followed The Peorian have probably wondered why nothing on the pages have changed in so long. I looked at it today and saw what the most recent articles were and realized just how long it has been.

Eight months ago, Feb. 24, I had an outpatient procedure done to correct a flutter in my heart. The procedure, a cardiac ablation, was supposed to be an easy fix, though somewhat invasive. Unknown to anybody, however, was that I had pneumonia at the time. Infection set in and in the wee hours of the morning of Sunday, Feb. 26 I woke up because I couldn’t breathe.

My wife called 911 and within 30 minutes I was in the emergency room at OSF; I was comatose and had been intubated. After 12 hours and the diagnosis of septic shock, I was moved to ICU, where I stayed for nine days, mostly unconscious.

It was the first – and only, I hope – experience of waking up to find I lost a period of time. In this case, I lost a week from the time I arrived to the time they woke me up after removing the breathing tube. I was scheduled to be in a play at Corn Stock Theatre and the day I went in was the “tech Sunday” for the show. Opening night was Friday, March 3. When I awoke in ICU and mentioned tech Sunday to my wife, she broke the news that the show, with somebody else in my role, opened two days earlier.

Because of the sepsis, four organs failed – my heart, kidneys, lungs and liver – and at one point I was given last rites, or whatever they call it these days. I don’t remember it; I was out. I also don’t remember that all my siblings drove to Peoria and the visits from them and my children, grandchildren and close friends. I’ve seen photos of how I looked, bloated like a whale because my kidneys weren’t working, and figured it scared a few of them.

You know, that sepsis is bad stuff. It can kill and often does.

I was in the hospital about a month, which included dialysis until my kidneys regained enough function to let me stop. I got to come home instead of to a nursing home for rehabilitation only because my wife Sue, without whom I would not have survived, had been laid off from her job a couple weeks earlier and would thus be home with me 24 hours a day.

What followed was a summer of follow-up doctors’ appointments, a boatload of blood work, chest and abdominal X-rays, EKGs and echocardiograms, etc. I learned my kidneys are permanently damaged and will never get back to full function, meaning dialysis may be in my future. My heart was damaged, as well, and is finally functioning well enough to return to my job. At the end of May it was functioning at less than 35 percent, which is kinda scary to hear. The cardiologist said that was the same as it was when I was in ICU.

We learned a lot, Sue and I. That includes how much a couple can need each other without being needy with each other. When I was lying there unable to communicate, it became apparent to Sue that neither of us had a will, including a living will, and that I took care of paying some of the bills that she knew about but not where to find the information about them. Because we both had been married before and at first had certain obligations to those previous marriages, we still had separate checking accounts. That was one of the first things remedied. We also took steps to cut costs since I was on long-term disability – things we probably should have done long before, such as refinancing the mortgage.

Throughout this ordeal I also learned how powerful prayer is as well as the devotion of a wonderful and strong spouse. Sue is my rock. I learned how great my children and stepchildren are, how loving my grandchildren can be, that I have some terrific friends, and I was able to revive some good friendships that had become strained.

Well, I am back and looking forward to renewing The Peorian. We will have a focus on area business and include national wire stories that could have a local impact. Keep sending me your news tips.

I hope you keep reading and get others to do the same.

Caterpillar reports strong third quarter

- Details

- Published on 24 October 2017

- Written by Paul Gordon

It was one heckuva third quarter for Caterpillar Inc. and the company expects the good financials to continue to the end of the year.

It was one heckuva third quarter for Caterpillar Inc. and the company expects the good financials to continue to the end of the year.

Caterpillar on Tuesday reported a third quarter profit of $1.95 a share on revenues of $11.4 billion, well ahead of the numbers posted in the third quarter of 2016, of 85 cents a share on revenues of $9.2 billion.

Through the first three quarters of 2017 Caterpillar has made a profit of $3.44 a share on revenues of $32.6 billion, compared with a profit of $1.88 a share on revenues of $$29 billion a year earlier.

The company attributed the improvement largely to higher sales volume and expects it to continue through the fourth quarter. To that end Caterpillar upgraded its outlook for the remainder of the year, now calling for a year-end profit of $6.25 a share, up from $5, and sales and revenues of $44 billion, up from a previous forecast of $42 billion to $44 billion.

"Higher sales volume and our team's focus on cost discipline resulted in improved profit margins across our three primary segments," said Caterpillar CEO Jim Umpleby.

“As a result of our team's strong performance, we are raising our 2017 profit outlook," he added. "We are executing our new strategy for profitable growth based on operational excellence, expanded offerings and services."

The company said it sees continuing strength in several industries and regions, including construction in China, on-shore oil and gas in North America, and increased capital investments by mining customers. “We are working with our supply chain to increase production levels to satisfy customer demand for those markets that have improved,” the company said.

The third quarter results beat the expectations of Wall Street analysts who had forecast a profit of $1.27 a share on sales and revenues of $10.6 billion.

Caterpillar stock price rose nearly 5 percent in trading on the New York Stock Exchange on Tuesday, closing at $138.24. The stock hit a 52-week high of $140.44 earlier in the day. Trading volume was high with nearly 19 million shares trading, well over the average volume is 3.4 million shares a day.

Caterpillar reported improved sales in all its segments, including resources industries, where the mining business is camped. After several years of losses, including a loss of $77 million in the third quarter of 2016, that segment showed a profit of $226 million this year.

Construction Industries still was the driving force and the company’s third quarter profit in that segment was $884 million, compared with $326 million a year earlier. Sales were up 37 percent in that segment and in each region Caterpillar serves.

One of the key movers in that segment was China, where the GDP has remained solid throughout the year.

The Energy and Transportation segment had a profit of $750 million in the third quarter, compared with $572 million in 2016, as sales and revenues improved 12 percent.

Amy Campbell, Caterpillar’s director of investor relations, told reporters this morning that there were no big surprises in any one segment over the others as all showed steady improvement year-to-year. She said company strategies for cost discipline helped build strong margins in all the segments.

“All three segments have some great stories behind their improvement,” she said in a conference call with reporters, the first such call since Caterpillar moved its headquarters from Peoria to Deerfield.

Campbell remarked that demand has been up in all regions, enough so that the company is in a hiring mode once again after reducing employment numbers by the thousands the last few years.

“We are hiring again to meet these higher levels of demand, including in the Peoria region,” she said.

At the end of the third quarter, Sept. 30, Caterpillar had 96,700 full-time employees. While that is 400 below the number of full-time employees a year earlier, the number of flexible employees was up by 6,500 year-to-year, giving the company a worldwide total of 114,900 employees. Campbell said the company’s plan is to move many of those flexible employees to full-time status.

Employment in the United States was 49,700 as of Sept. 30, with employment outside the U.S. at 65,200, the company said.

Normally Caterpillar would use its third quarter financial report to issue a preliminary outlook for the next year, in this case for 2018. But it did not do so this time and Campbell said that’s because the company has been focused on operating performance for the first nine months of 2017.

“We are putting together our growth strategies for 2018. We will revisit 2018 in January,” she said.

Caterpillar had $90 million in restructuring costs in the third quarter, which includes costs incurred by the employee reductions, and through three quarters those costs topped $1 billion. The company expects restructuring costs to be about $1.3 billion for the year.

Molly Crusen Bishop: My grandpa witnessed history

- Details

- Published on 03 June 2017

- Written by Molly Crusen Bishop

There were two guys named Charles living on Barker Avenue on Peoria’s West Bluff in the 1890s. One was Charles Duryea, the father of the American automotive industry, and the other m was my grandfather, Charles Needham.

There were two guys named Charles living on Barker Avenue on Peoria’s West Bluff in the 1890s. One was Charles Duryea, the father of the American automotive industry, and the other m was my grandfather, Charles Needham.

Charles Needham was born in Peoria in the early 1880s to Patrick and Ellen McGowan Needham, first generation Irish Catholics. Patrick worked for the Rock Island Railroad Line.

Charles Needham was born in Peoria in the early 1880s to Patrick and Ellen McGowan Needham, first generation Irish Catholics. Patrick worked for the Rock Island Railroad Line.

Charlie Needham attended a school originally called the Fifth District School on Moss Avenue. It was later called Franklin, though not the Franklin on Columbia Terrace. The first Franklin/Fifth District School on Moss was authorized by the Peoria District School Board in 1853, with the school being completed the following year.

Charlie Needham describes attending in 1890 at an old-looking school of eight to 10 rooms. It had wooden walkways to it and around it and each room was heated by a large coal-burning stove. Toilet facilities were located about 300 feet behind the school. The Franklin school on Columbia was built around 1892, and the old Franklin on Moss Avenue had its name changed to Columbia. It was later torn down to build the Washington school, which is now a Buddhist temple.

Charlie Needham describes attending in 1890 at an old-looking school of eight to 10 rooms. It had wooden walkways to it and around it and each room was heated by a large coal-burning stove. Toilet facilities were located about 300 feet behind the school. The Franklin school on Columbia was built around 1892, and the old Franklin on Moss Avenue had its name changed to Columbia. It was later torn down to build the Washington school, which is now a Buddhist temple.

Charles Duryea was born in 1861 near Canton, Illinois. He and his brother Frank were originally involved in bicycle manufacturing. Frank was already in Peoria when Charles arrived in 1892 to launch a bicycle he had designed and for the brothers to work with the Rouse-Duryea Company.

The brothers co-founded the Duryea Motor Wagon Company. Charles was the engineer of the first working American gasoline powered automobile, and my grandpa Charlie Needham witnessed this first hand as a young boy.

“Speaking of automobiles, I might add that Charles E. Duryea, was given credit as the inventor of the first usable automobile, resided at the time he worked on his first car at [then} 208 Barker Avenue, and worked on his machine in his ‘barn’ as in those days we didn’t have garages, we had barns. I saw Charles Duryea test driving his horseless wagon up and down Barker Avenue trying it out,” Charlie Needham.

Charles and Frank Duryea successfully crafted the gasoline powered three-wheeled, three-cylinder horseless carriage known as the Peoria Motor Trap, test driving it up and down Barker Avenue on Peoria’s West Bluff. In 1898, Charles developed the Duryea Manufacturing Co. in Peoria Heights with plans to mass produce the vehicles. About 13 traps were built when the company began to have financial problems and went out of business. The brothers ultimately went their separate ways, creating separate companies.

Charles and Frank had a long public dispute on who should get credit for inventing the gasoline powered automobile. Charles Duryea claimed himself as the “Father of the American Automotive Industry.” One of their early automobiles is in the Smithsonian Museum. Another one was bought by a group called “Bring Home The Duryea” to Peoria in 1992, after raising the $125,000 dollars to purchase from a private owner. The Duryea trap was located in the downtown library in Peoria until it was brought to the Peoria Riverfront Museum in 2012.

Charles Duryea died in 1938 and my grandfather Charles Needham died in 1957, long before my birth in 1972. I was raised in the house on Barker Avenue from which my grandpa witnessed history in the making: The house Charles Duryea built and test drove his horseless carriages from is now 1512 W. Barker Avenue, and is for sale, incidentally.

I will write about another event in local history next week called The West Bluff Water Tower Disaster. This story includes my grandpa Charlie and life-altering events he endured as a boy on the west bluff of Peoria on March 30, 1894.

Molly Crusen Bishop: The West Bluff Water Tower Disaster

- Details

- Published on 18 July 2017

- Written by Molly Crusen Bishop

The West Bluff Water Tower Disaster

By Charles Needham and Molly Crusen Bishop

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories from Molly Crusen Bishop that will be based on the essays about the West Bluff by her grandfather, Charles Needham.

Charles Needham was born to Patrick and Ellen Needham in Peoria in the 1880s. Patrick worked for the Rock Island Railroad line and later at the Glucose Factory, which was a part of the distilleries. He was a night watchman and later a Teamster, driving the horse and carts loaded with barrels, once they were done with that process in the distillery.

Charles Needham was born to Patrick and Ellen Needham in Peoria in the 1880s. Patrick worked for the Rock Island Railroad line and later at the Glucose Factory, which was a part of the distilleries. He was a night watchman and later a Teamster, driving the horse and carts loaded with barrels, once they were done with that process in the distillery.

They lived on Barker Avenue, on Peoria’s West Bluff, building the house in which three generations of Needhams, and ultimately Crusens, were raised. Charlie attended Bradley Polytechnic Institute. He had a nice job as a traffic manager at Larkins and was also a paid political speech writer in Peoria in the 1930-1950s, until he passed in 1957. He wrote several essays with first-hand descriptions of what life was like on the West Bluff. My grandfather was also a staunch Roosevelt Democrat, incidentally.

I have read through his essays, and have done extensive research of my own as well, and feel comfortable retelling his stories with my own information and words, relaying the commonality I share as a writer with my grandfather; not only his story-keeper, but a storyteller as well.

The West Bluff of Peoria was filled with prairies and cornfields on the west side of the west side, shall we say. The Uplands were cow pastures and crops, so the area between what is now University Street and Farmington Road, was sparsely settled in the 1880s. There was a boardwalk that ran along Russell Street. Bradley Park was just a large stretch of woods and the territory later known as Summit Boulevard was a dump for scrap.

The West Bluff of Peoria was filled with prairies and cornfields on the west side of the west side, shall we say. The Uplands were cow pastures and crops, so the area between what is now University Street and Farmington Road, was sparsely settled in the 1880s. There was a boardwalk that ran along Russell Street. Bradley Park was just a large stretch of woods and the territory later known as Summit Boulevard was a dump for scrap.

Charlie remembered a house called Harper House, on Main Street, which the neighbors referred to as an “Old ladies home.” There were random homes scattered about and young boys like Charlie could find baseball diamonds and football fields everywhere. Bradley Avenue was formerly called Hansel Street and University Street was formerly called Bradley. Charlie recounts he could stand near St. Mark Church and see all the way to the back of West Peoria, near Swords hill, as a young boy.

“Here begins the saga I have entitled, The West Bluff Water Tower Disaster,” states my grandfather in the essay under his byline, Charles Stuart Parnell Needham.

Charlie was a young boy of nine on what was a sunny spring day on Peoria’s West Bluff, on March 30, 1894. Charlie and many other children were enjoying a school spring vacation day, playing near Main Street and the Bourland area.

St. Mark’s old rickety wooden rectory house was located near 401 and 403 Bourland Avenue. Father O’Reilly was the pastorate and Archbishop Gerald Bergen lived on College Street near where this tale takes place.

On this glorious spring day in 1894, Charlie and the other children roamed near where there was a large water tower, near then 404 S. Bourland. There were scattered houses near there and Underhill, but many open lots as well.

This water tower, or what was known as the West Bluff Standpipe, was made of steel and wood and had been built to give more water pressure to the surging population on the west bluff.

Children were running and playing, powerful businessmen in suits with long coats and beautiful hats were walking to and from their businesses, and ladies, with their long dresses and fancy hats, commanded their children this way or that, leaving the local corner market. Charlie refers to the top of Main Street as the top of the hill.

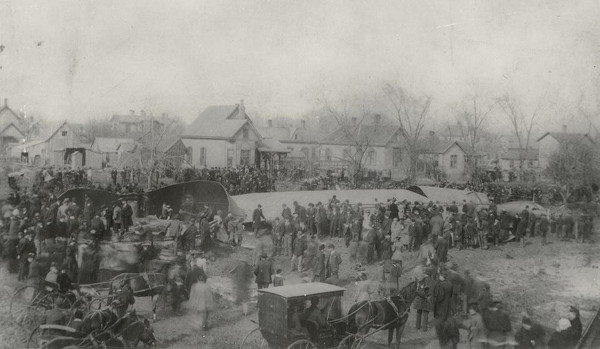

The water tower was about 30 feet in diameter and approximately 130 feet high. Leaks were springing up on the massive tower and strong and busy men climbed up on 30-50 feet ladders, hammering, caulking, and plugging up the leaks as best as they could. There was major pressure from the millions of gallons of water inside the tower and as the men were pounding, a disaster was about to take place.

Charlie and about nine other boys aged 9-15 were playing in the street just beneath the tower and watched the men work. Trolley cars and horses and buggies could be heard and seen, and smelled. Main Street was just a block or so away.

The strain on the riveted steel in the legs beneath the tower, on the lower portion of the tower, caused the steel and wood beams to break with a thunderous explosion, causing the water tower to burst into a tsunami in an eastward direction.

The wood splintered instantly into hundreds of pieces and the steel broke apart into jagged spikes and sheets. The wood, the steel, the water came down upon the boys with great force of doom. Charlie’s friend Frank Hogan, an altar boy at St. Mark, was caught in the chest by a sheet of steel and was sliced into two pieces instantly. Charlie’s other friend, Frank Caldwell, who lived across the street from Frank Hogan, was crushed by a large piece of wood that hit him like a battering ram. Frank Caldwell languished and suffered for two days before dying from his injuries.

The other boys were badly injured, and they were all half-drowned.

“I heard the splintering and boom and saw the water approaching us rapidly. I was carried out of the way of a large piece of jagged steel in one second when the force of the water grabbed hold of me and swept me away. The water carried me over a block down on Bourland, and near Windom Street, and then the water recessed back down the street toward the Main Street Hill,” Charlie Needham wrote.

The wave of water moved him towards College and Main, where he was able to see above the water enough to see the streetcar trolley wire pole. He grabbed the top of the pole to stop himself from being carried along with the wave any further. Some men standing in knee-deep water managed to get hold of him and pulled him out of the wave. His clothes were ruined and he was half-drowned, but there was not a scratch on his body.

The water stopped just at the edge of the alley near St. Mark’s rectory, according to Father O’Reilly’s housekeeper Miss Ellen Head. She saw the force of water coming and believed it was going to sweep the rickety old rectory away with it. She saw the water stop at the alley’s edge and head toward Main Street Hill.

There was another two-story house to the south of the tower. A mother left her sleeping baby on the second floor prior to the explosion to go next door to borrow a much-needed missing ingredient for her day’s baking. That’s when the water tower exploded and a large sheet of steel hit her house crashing into the second story where her baby was sleeping. The baby was safe, but the damage incurred made it impossible to retrieve the baby from inside the house. A ladder had to be put up to a window to get her baby to safety.

Charlie was an altar boy for Father O’Reilly at St. Mark’s early little wooden church, with Frank Hogan and Frank Caldwell. They served at weddings together and he stated that there weren’t many weddings in the little church in the early days. The boys would rotate serving at masses and baptisms and Vespers and Benedictions. I am very saddened the two Franks lost their lives so young. I am very blessed Charlie had a guardian angel of some sort and thankful to be here today, being a story keeper and a storyteller because he survived the West Bluff Water Tower Disaster over 123 years ago and held a small piece of Peoria’s West Bluff history in his memory and in his written word.

Study the beautifully haunting photo that shows the aftermath of this tragic experience my grandfather endured. I am especially thankful to Christopher Farris and to the Peoria Public Library Local Historical Collection, with their Grassel Collection. This photograph is titled the West Bluff Standpipe.

This is the first in a series based upon my grandpa’s essays from the 1880s and 1890s about the West Bluff and thorough and extensive research of my own over the past four years.

Morris named to head Riverfront Museum

- Details

- Published on 22 February 2017

- Written by Paul Gordon

The Peoria Riverfront Museum decided to stay home for its new leader this time.

John Morris of Peoria, a former Peoria City Councilman and current director of The Ronald W. Reagan Society at Eureka College, was announced as the new president and CEO of the museum, beginning April 10.

Morris, who once worked at Lakeview Museum, was selected after a national search that began with the resignation last October of Sam Gappmayer, who took a position at the John Michael Kohler Museum in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, after less than three years in Peoria. Gappmayer came to Peoria from Colorado Springs, Colorado.

The search was conducted by Kittleman & Associates and the museum’s board of directors, which voted unanimously to offer the position to Morris, said chairman Sid Ruckriegel.

The board said Morris’s experience as a philanthropic administrator who has held management and board roles in public media, higher education and the arts, and served in public office, all served him well in the search process.

“We are pleased to welcome John Morris to Peoria Riverfront Museum,” said Ruckriegel. “John brings not only his fundraising experience but, having started his career at Lakeview Museum, he also understands the key role that the museum can play in the future vitality of Peoria.

“The museum has increasingly become a place for our community to enjoy new and meaningful experiences, to learn hands-on and to grow. Just this past Sunday (Feb. 19) during Engineering Day, more than 3,700 people filled the halls,” said Ruckriegel. “John is dedicated to building on that momentum.”

Morris, a Peoria resident, is a 25-year veteran of higher education, cultural and civic philanthropy, and nonprofit management. He began his career as the development director for the museum’s predecessor, Lakeview Museum of Arts and Sciences, where he created the first major giving society and raised funds to secure more than 25 exhibitions and programs.

For the past decade, Morris has been at Eureka College as director of the Ronald W. Reagan Society – the only national donor network of its kind in higher education. Working with Eureka’s former president J. David Arnold, Ph.D., and current president Jamel Santa Cruze Wright, Ph.D., Morris built key partnerships with presidential libraries and scholars, and helped create the Mark R. Shenkman Reagan Research Center.

"The Peoria Riverfront Museum board has an exciting vision to serve all Central Illinoisans with the finest multidisciplinary museum in the nation,” said Morris. “It will be a great honor of my professional career to work with museum staff, donors, community partners and the public to help achieve this vision.

“I’m committed to the museum’s mission as we focus on people and how we can use our museum to tell the stories that unleash their full potential," said Morris.

Morris also spent 10 years as vice president of WTVP, Peoria’s public television station, where he led fundraising efforts that included two capital campaigns for one of the nation’s first digital stations and the current riverfront studio.

Morris served two terms as an at-large Peoria city councilman (1999-2007). He was an early advocate for riverfront development, and a supporter of the public library and the arts.

Morris served two terms as an at-large Peoria city councilman (1999-2007). He was an early advocate for riverfront development, and a supporter of the public library and the arts.

Morris holds Master of Public Administration and Bachelor of Arts degrees from The George Washington University in D.C., where he was a White House intern. His wife Cindy Morris is president of the Peoria Public Schools Foundation. Their son and daughter attend Eureka College.

Morris will take over from current interim president & CEO Debbie Ritschel, who was lauded by Ruckriegel for her work.

“The board and staff will always remain grateful to Debbie Ritschel, who has stepped in twice to serve as our interim director,” said Ruckriegel. “She has served and continues to serve not just our museum but also our entire community in many ways.”